It was a most unusual experience. Early last week two stylish and professional women came into the gallery where I was sitting that day. They said they represented the BBC and were looking for a place and a person to dialogue with an artist from England. They couldn’t tell me his name, only that he’d had some problems and was now “coming back.” I listened for awhile. It didn’t sound like a scam, so I agreed to help them out.

Over the next two days I received phone calls from other “producers,” seemingly more to check me out, that I was the right one to do this and that I’d dependably be there.

On Thursday I worked the gallery again. It’s the Sandstone Gallery in Laguna Beach where Anne and I both show our work. By late afternoon the two young women showed up, then three camera men, a sound man, and two more producers, men. Things were rearranged for best shooting angles. Then, finally, he appeared, the artist from England. Let’s call him Mark, as I’ve forgotten his real name. I still didn’t know anything about him besides what I’d first been told. Immediately camera were rolling.

Mark was a tall fellow, slightly bald, slightly crooked of tooth, large ears, large voice, and occasionally a large laugh—though somewhat forced and a little countrified. Of course he spoke with a British accent. (Or do I have an American accent?) He wore a medical neck brace, which I never quite got the story about. He was tall, and in fact that was my first comment in sitting down together, “How tall are you?”

“Six-foot, four.”

“Wow, I wonder what the perspective is like from there, looking over most people’s heads.”

“Yeah,” he said, “When I was inside . . .”

“What? Inside what?”

“You know, in the big house.”

“Prison?”

“Yeah.”

So this was the mystery . . . the part I hadn’t been told. He’d been in prison, was just out, he was an artist, and the BBC was tracking him to see if there would be a story. If he was a great artist, they’d be in on his development. Even if not, it could be an interesting story to see how an ex-prisoner attempts to rebuild his life using art as his vehicle. The producers had told me they didn’t know what would happen with the footage, whether it would eventuate into a documentary, a TV series, one program, a movie or what? Mark would be in the States for one week. He would meet various people, including at least one gallery. This was his first day; this was his first gallery.

I liked him. And he’d apparently been looking forward to meeting me. He even carried a clipboard with a sheet of questions. Early on he wanted my opinion about whether one should tell interested clients his background. I affirmed that he should. People want to know who it is that made the art, what’s their story, how they happened to become who they are. If it’s a unique story, all the better. And when they buy the painting and display it, they’ll tell the same story to their friends.

He listened carefully to all this and thanked me for it. But there was another question: “How much do you tell them about how you made it?”

“Same answer,” I said, “that is if they care. I tend to tell people about my process of a given painting whether they care or not, because I think it’s interesting. So, yes, tell them.”

He thanked me for that too. Then he asked me how to succeed as an artist.

“That’s a harder one,” I told him. “There’s no one answer. First,” I said, “Define success. If it’s all about money, how much? How consistent? Maybe there’s never enough? If you define success as happiness it’s easier, you may be there already.”

He thought that was interesting. “But you’re successful,” he said, making a broad sweep of all my paintings on the wall.

“I’m successful on the latter part,” I said, “but you have no idea how many of these paintings are actually selling . . . and the same with all the seemingly successful artist in the galleries up and down the street.”

“Okay,” he got that, but what he really wanted to know was whether he could hope to make some money, some real money, some consistent real money on this new venture. I told him there was no one way that I know of, that every artist finds his own way . . . or doesn’t.

One thing I did tell him that I’ve discovered and that I tell other artists, “Go through every door that opens, and . . .” he broke in with his big rowdy laugh and finished my statement: “Bash down the others.”

It was, “knock on all the others,” that I was going to say.

“Why were you in prison?” I was curious but didn’t know if he’d want to divulge.

“I was naughty,” he said.

“Okay.”

“I was naughty nine-teen times!” He laughed.

“But I never hurt no one.” He emphasized this. “I’m tall but I’m not strong; I’m weak.”

He wanted to know how I got into art. I told him a brief version of my story, which he found interesting, and I was interested in how he got started.

“It was inside,” he said.

How long had he been there?

“Just 20 years.”

“Twenty years!?!” He passed it off as if comparing to others with far more.

He told how one day he was just so angry with everything he took it out on a wall, marking it all up. When the guard saw it he said, “That’s good art! I’m still going to wash it off, but you’ve got ability.”

That got Mark’s attention.

After that he said he started doing it more, drawing on whatever he could find. But it really began when he got to acting out again and they threw him in solitary.

“Solitary confinement?

“Yeah. Have you ever been in solitary?”

“Not yet,” I said.

“It bad,” he said, “just those padded walls. I had some books and stuff, but then I got an attitude and they took all that away too, just to really punish me. I was in solitary for three months. Can I show you some of my art?”

“Of course.” This is what artists do, they show their work . . . especially to another artist, in a gallery. He’d brought with him a standard portfolio bag for flat art and a relic of a small suitcase, the kind you might find in a consignment shop for someone wanting a touch of nostalgia. He opened it and brought out a small piece of wire sculpture mounted on a block of wood. It was really quite fine. I wish now I had a photo of it, and of his paintings, and of him, and of us together. But I didn’t think of any of that. Wouldn’t there be plenty anyway? The cameras were rolling the whole time . . . though we’d become completely oblivious to them.

I got down on my knees for close inspection of the little sculpture. It was of a prison bed, complete with prisoner in it and even a piece of torn muslin for the “sheet.” I thought, “Wow, he really is an artist.” But still quite naive.

He called it his “two dimensional work.”

I said, “No, that’s three dimensional.”

“Two,” he argued.

“No, the work on the walls is two dimensional, with height and width. This has hight and width and depth, it’s three-dimensional.”

“Whatever,” he said.

Later he showed me a colored drawing of a two-decker British bus which he called a “self-portrait of a bus.” Again I had to correct. “It’s not a self portrait unless you’re in it. There’s nobody at all in your picture.”

“Yeah, but I did it. It’s a self-portrait.”

“Whatever.”

He showed me more of his paintings. One was a rear view of prisoners from slightly above, another of nature from behind bars complete with heavy lock, another was of one of his two daughters . . . “from two mothers,” he said, “one I don’t speak to. But I love my daughters.”

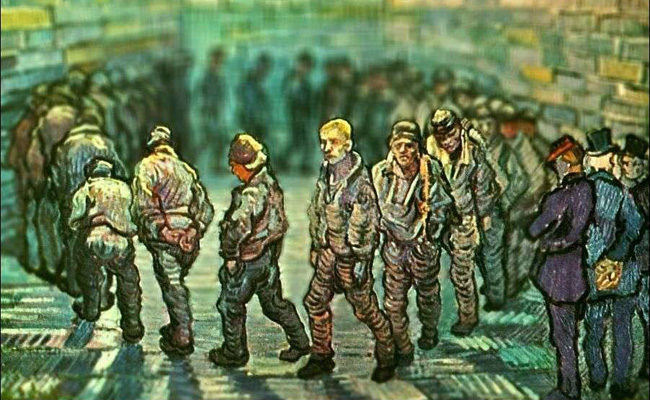

For the most part the colors were in brown tones, the substrate was manila file folders, some with labels in the corners that had been torn off. The perspective in the drawing was good, and I saw no evidence of any pre-drawing, further impressing me. I told him one reminded of a Van Gogh where he had painted prisoners in an exercise yard. Mark found this very interesting. Of course Master Vincent was never in prison, but often dignified the down-trodden.

Detail of Van Gogh’s Prisoners Exercising.

“Can I tell you how I made them?

“Of course,” I said.

“Feces,” he said, and waited for it to sink in.

“Feces?” I repeated, as the next level of this whole odyssey began to take shape.

“I had nothing else, he said, “that and a little bit of blood,” (and some other fluids the body produces that I won’t mention here).

“What did you use to put it on?” I asked, the line work being too fine for finger application.

“I made a brush,” he said.

“Of what?”

“Hair. My own.”

I admit I’m as stunned now as I recount it as I was when I was first hearing it. It’s no wonder the producers wanted me to know nothing before we began. And no wonder they’d done quite a bit of vetting of me, that I’d be one to handle it all in stride.

The fact is, I did. Though there’s an element of disgust in it all, there’s something positively creative and eminently resourceful about it. It’s no wonder he’d had these questions about how much to tell, of background, of methods.

Of course that is the story. He did have ability. But really no more, as I reflected later, than a talented high schooler who should be encouraged to develop it. But his story of how he discovered it and what he used to overcome the extreme limitations of resources, not to mention personal freedom, that’s the story.

He asked me if he should keep on using that approach, now that he’s out, or if that would be, “too much of a gimmick?”

I agreed it would be. But who knows? A lot of “artists” have stooped to a lot of things and got rich snowing the public. Artists with a “con” in the front. Only here it’s an Ex-con artist. (My joke. Don’t know if he’d have laughed.)

Our interview was at a close. I gave him a few more pieces of counsel as to how to succeed, in his case, mainly to be patient and not be tempted to go back to his old ways (like bashing down doors). In it all he thanked me, shaking my hand numerous times, like I’d really been an encouragement.

In his gratitude he left me with a boisterous, “If you’re ever in South London, just tell them you know Mark Cline. You’ll be taken care of.” (That was the first I heard his last name, and in fact I’ve forgotten it now. I only think it was Cline.)

I must say I enjoyed the whole process, and the crew, as they gathered up their equipment, seemed satisfied with what they got.

It was on the way home I got to wishing I had got his full name and some indication as to when it might air on BBC’s Channel 4. Later I put in a call to one of the young women that had first approached me. With no response, I called the other. I did this for a number of days, leaving messages, sending texts, and growing a little annoyed that though I’d been cooperative and dependable, I wasn’t getting the courtesy of a call back. After a week I finally got a recording from one simply saying, “This phone number has been discontinued, good by.” What? I punched in the number of the other woman and, again, “This phone number has been discontinued, good by.”

What was that about? A scam? But to whose profit? Very strange.

The whole thing, really.

If I ever hear more, or learn if anything is to be aired, I’ll let you know.

Meantime, here are a few points that might benefit:

Be resourceful—you may have more than you know very close at hand.

Measure your success by your happiness over your income, you might be closer than you think.

Go through all the doors that open, and knock on all the others. (And don’t be tempted to bash them down.)

2:35 pm

Good God!

6:48 pm

wow, interesting! looking forward to more.

9:22 pm

This was interesting & very strange.

Thank you for sharing & giving us your thoughts on success.

It’s a good thing they wandered into your gallery!

8:33 am

Quite the story. Seems like a creative producer could do something with that.

9:24 am

I think you were conned. Possibly a fake story. You should have checked up that this really was the BBC, by getting in touch with them.

2:53 pm

wow! a scam but of what profit? call BBC! Tell them you’d like a commission. You earned it.

4:25 pm

I don’t see anything of a scam here. I see a person whose self-worth is measured by the money he can make. Unfortunately, like most of us. And he’s being exploited by a communications company. (If there’s a scam, that is where it lies.) If he’s an artist, he might thank God for his ability. If not, he might ask God to show him what he is. Too bad that you have no further contact with him. You would be the kind of friend that he needs.

7:28 pm

Great experience! Looking forward to any further contact or any film to view.

4:42 pm

Wow! Scam or not, it’s a really good story. Hope they do contact you so we can read more. :)

5:35 pm

This story is fascinating and mysterious…worthy of a literary magazine. Whether or not the artist is totally honest, he is real and you, Hyatt, were in the right spirit to give him respect and your best advice. What is there to lose when you take a fellow man at face value (unless of course he cons you out of your life savings)? Thanks for sharing your experience!

9:25 pm

Well, good stories come to those who know to tell them… great read as always, Hyatt!

8:59 am

Great story, Hyatt! I’m looking forward to seeing how this develops. Please keep us updated.

8:27 pm

Perhaps they were using temporary phones here and, if they are no longer in the USA, that may be why the numbers are disconnected. All sounds a bit strange though. Are you sure it wasn’t a dream?! ;)